UPDATES: 12 April 2018, 11:20 a.m.: This article was updated with new reporting and additional analysis.

When Pussy Riot, Russia’s premiere feminist art collective known for its rotating and balaclava-clad cast of political performers, announced a gig in Santa Cruz, I bought a ticket and readied myself for something historic.

Night of, I dressed for both punk show and politically rally, but I couldn’t have prepared for what was ultimately delivered: a total letdown.

Tickets cost $25, and Pussy Riot, which on Tuesday was just Nadya Tolokonnikova and another unidentified DJ, played an underwhelming 40 minute set. Surrounding the evening was a hailstorm of misinformation regarding scheduled times for doors and music, and some late-comers, perhaps expecting an opening act, arrived at the venue as Pussy Riot left the stage, missing the performance completely. Ranging from disappointed, to angry, to perplexed, many sought out Catalyst staff, wanting their money back.

Pussy Riot failed to meet our expectations, varied as they were, but as I peeled back the layers of my disappointment, what I found was not a laundry list of injustices committed by an artist I did not know well, but Santa Cruz, my city and my home.

The aftermath of the show was a total flip from the excitement that kicked off the evening, when Tolokonnikova, under the bright wash of white strobe lights, took the stage with “Make America Great Again.” More pop than punk, the track asserts that the U.S.A might be great if it learned to listen to women and stop killing black children. It’s participatory in that it asks its listeners to envision a better future: “What do you want your world to look like? What do you want it to be?”

Maybe it was that the crowd hadn’t been warmed up, or perhaps attendees were expecting something undeliverable, but there seemed to be a disconnect between the performers and the crowd. Some danced, others stared at Tolokonnikova, whose erratic movements mirrored the chaos of the videos projected behind her, through the screens of their iPhones.

Pussy Riot performed just two more songs before leaving the stage for an intermission.

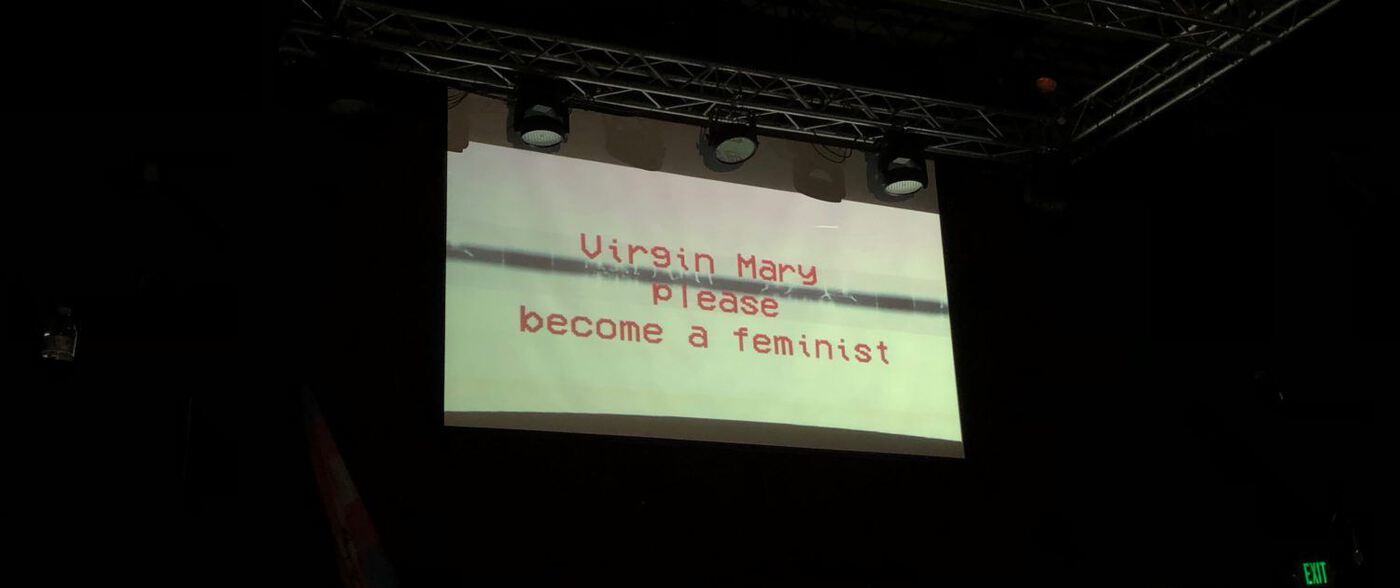

While the duo was away, black and white line drawings of churches flashed across the screen. Written over the pictures in red letters were lyrics from Pussy Riot’s infamous Punk Prayer: “Virgin Mary please become a feminist. Virgin Mary please get rid of Putin.”

In 2012, members of the collective were arrested after performing an iteration of this song in Moscow’s largest cathedral. The action, which lasted fewer than 60 seconds, landed Tolokonnikova and her co-conspirator, Maria Alyokhina, in a Russian penal colony, where they served twenty-one month sentences for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.” An amnesty initiated by President Putin ahead of the Sochi Winter Olympics, freed the duo in the final weeks of 2013.

The group performed a few more songs in Russian and English, ending with “Straight Outta Vagina” from their 2016 EP, xxx. Despite its intentions, the song has received backlash for its genital-centric construction of womanhood, which in more progressive circles is recognized as a trans-exclusionary brand of feminism.

And if the lyrics weren’t enough to prove this critique valid, for a brief encore, Pussy Riot came out waving the Transgender Pride Flag. Written on it, the slogan: “Pussy is the new dick.” This strange spectacle was greeted with cheers and the blinking of many cameras.

After the show I caught up with David Anton Savage, General Manager of the Rio Theatre and host of the long-running KZSC program Unfiltered Camels. He reported that Pussy Riot’s 40 minute set was, according to the sound guy, the second shortest show in the venue’s history.

While we talked, Savage was approached by a ruffled fan, who asked if we worked at the venue. When Savage said no, the man began to vent.

“My girlfriend and I drove down from San Francisco, spent two hundred dollars on a hotel. We came here for nothing.” A passerby recommended he leave a bad Yelp review. “For who?” he replied in earnest. “No one even cares about Yelp anymore.”

UCSC student Belle Holder, who’s followed the group since she was in middle school, expected a Pussy Riot show to be heavy on politics, not what she described as “old Russian club music.”

In the past year we’ve watched enough artists fall from their graces to know what disappointment feels like. It was easy to recognize its palpability amongst the crowd as it poured out onto Pacific Avenue.

But some attendees, like Tomás Lamar González, were more understanding. “In light of the fact that three of them were kidnapped a month ago,” he said, “I wasn’t surprised or disappointed.”

González was referring to reports that multiple members of the group, including Maria Alyokhina, were detained upon entering Russian-annexed Crimea on March 18. Alyokhina has not performed with Pussy Riot since speaking with reporters about her romantic relationship with Dmitry Enteo, a founding member of the ultra-orthodox, anti-LGBT Russian political group God’s Will.

Irony of this nature doesn’t sit well with many Santa Cruzians, who prefer to believe that the industries they support reflect their values. The cultural diet of the region is not so different. People here want to know that the art they consume is produced by those they wouldn’t be embarrassed to go to a protest with.

It is fair to say that Pussy Riot hasn’t always passed this litmus test. But what if, by asking these women to be our artists and our activists, we’ve set the bar impossibly high.

A society asks its creatives to represent both its deepest and most banal desires. Live the starving artist trope until, if you’re very lucky, or privileged, or both, it sustains you. We ask even more, and with higher stakes, of our social justice activists: just fight our heaviest battles for us. We’ll stand over here.

Current archetypes for this phenomenon are Emma Gonzales and David Hogg, who, with furrowed brows and powerful oratory, transition from civilian to generational spokesperson at the flash of a camera. In the shadows is their classmate, Samantha Fuentes, addled with PTSD after being hit in the face by bullet spray at Stoneman Douglas High School. On March 24th she took the stage at the March for Our Lives rally in D.C., and mid-sentence, as the world watched, vomited into her own hand.

Our culture is one that disproportionately applauds activists who, despite long hours, little pay, and immeasurable stress, suffer privately and not in public. But like Fuentes, Tolokonnikova’s foray into activism was result of injustices unimaginable to most Americans. She is under enough personal and political pressure to deserve the benefit of the doubt from a crowd that boasts as many privileges as the one gathered in Santa Cruz on March 27.

Not one-sided, disappointment is a relation between multiple parties. A crowd is nourished by the energy of its performers, and vice versa. But in some cases, when the relationship is more parasitic than reciprocal, a performer can appear drained by an audience. As was the case between Tolokonnikova and her iPhone-wielding, expectant Santa Cruz audience. The brevity of the show seemed to suggest that the disappointment was mutual.

In a very important sense, Pussy Riot did deliver last week. They set the stage for their fans to engage with ideas of political utopia, and when they posed the questions, “What do you want your world to like? What do you want it to be?” they challenged us to imagine it for ourselves.

They even offered some solutions. “Matriarchy now,” they had written on the screen during one song, and later, “God is woman and she’s bad and she’s queer.”

In one video projected behind the performers, a television anchor announced wish fulfillment news: “Donald Trump has been impeached. Five criminal cases have been brought against him.” And minutes into the next song, another news anchor, this time reporting from the Russia: “Vladamir Putin has escaped Russia during protests against him.”

“Anybody can be Pussy Riot,” Tolokonnikova said, her final words of the evening. “You can make your own band and start a concert.”

Pussy Riot, from the opening lines of their first song, invited us to take action. They created a space for us to organize, provided the soundtrack and lyrics to our protest, and from the first song, challenged us to envision a borderless, international community that brought corrupt leaders and institutions to justice.

Tolokonnikova has faced a lifetime of violence over the past decade, and was asking us, explicitly, to carry some of that weight. It was as though we’d left her to march alone.

Pussy Riot self-describes as a fake band. Tolokonnikova is not in it for the music; she’s a performance artist whose guerrilla collaborations with other artists and activists aim to shake the masses from the complicity of their slumber. And at the Catalyst last week, this is exactly what she failed to do.

But part of that wasn’t her fault.

To be disappointed in an artist is to believe they owe you something. To be disappointed in an activist is to idle in the safety of your privilege and offer a critique. It is to spend $25 to be a spectator at a political rally instead of inciting one of your own.

Pussy Riot chose a limited number of cities for its first ever North American tour. Their stop in Santa Cruz was nestled among dates in Los Angeles, Boston and Mexico City, cultural metropolises known for incendiary, if not revolutionary, spirits.

On this night, at least, Santa Cruz failed to provide the fire.

Written By: Robin Estrin (DJ Compost)